I do believe that the time slip story is one that will never go out of fashion — there is

so much history to explore!

We’re seeing a notable wave of timeslip novels in Australian children’s literature. I showcased some of them in Children’s Timeslip Novels by Australian Authors, added a Goodreads list called #LoveOzMG Timeslips, and wrote a longer piece called A Matter of Time which I also turned into a short podcast episode. No one has told me to shut up about timeslips, yet, so here I am again with reading notes on a recent novel.

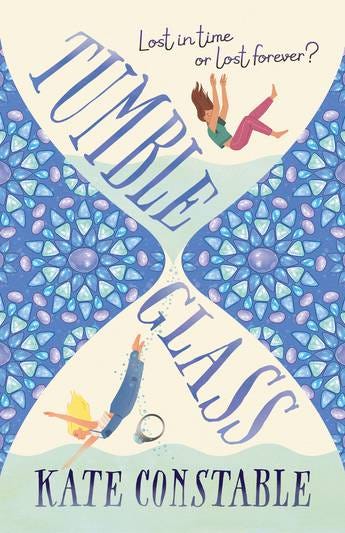

Let me introduce you to one of the best timeslips I’ve read in a long time. Tumbleglass by Kate Constable, published by A&U.

Tumbleglass is the story of a house.

It’s a house that is over a hundred years old. A steady presence for one family after another, through wars, fashions, and political and social change. But while every house has its foibles, its own smell and feel, this house has a special kind of crack that allows time travel to take place. And one day, 13-year-old Rowan and her 19-year-old sister Ash tumble unexpectedly into that crack and land in the year 1999, slap-bang in the middle of a party (which is the first of several lovely moments of humour for us older readers).

I asked Kate how she came to write not just one but several timeslips since her debut in 2002. She said:

I’ve always been a fan of timeslip stories ever since I first encountered them. Philippa Pearce’s Tom’s Midnight Garden has been a huge influence on my writing, but I also loved Alison Uttley’s A Traveller in Time and Lucy M. Boston’s Green Knowe books, which are a cross between ghost stories and timeslips — and feature several generations of children in a single house. I’ve always been fascinated by history, and especially by old houses and thinking about all the people who have passed through their walls.

Family Dynamics

There were two aspects of this novel that bowled me over — no, make that three and I’ll get the first out of the way quickly: the writing. Kate Constable’s prose is absolutely delicious.

Secondly, I loved the clever family dynamics and how the timeslip worked intimately with those. The relationship between mothers and daughters is important but lightly done. Even more interesting to me was the relationship between Rowan at 13 and Ash at 19. Tumbleglass has the younger teenager in the central role, with her close-up view of older teenage life through Ash who has a job, boyfriend and uni degree. Early on in the story, Ash becomes stuck in 1999 and cannot be retrieved without her younger sister embarking on a series of time-travelling missions to different times: 1900, the 1940s and 1972.

With Ash gone, Tumbleglass explores the loss a young teen may feel when their much-loved older sibling “grows out” of home. The reader may also observe that an older sibling can fail to grasp the impact of their leaving. I found this a beautiful, unusual storyline. Perhaps it especially made its mark on me as the eldest child who’s always done the leaving.

But Ash’s departure clears a pathway for Rowan to be in charge, to be the key to what happens next. Rowan can “try on” independence and responsibility a bit like wearing her big sister’s coat. We explored a similar theme in Elsewhere Girls by having Cat, aged 13, swap bodies with Fan, aged 17.

When children think about “being older”, they can’t really imagine a different mindset but they imagine being able to do different things, being treated differently because they look older. So in these types of stories, whether the main character becomes older-looking through some kind of transformation, or experiences an older lifestyle through a sibling, it’s an opportunity to “try on” the future — in the case of timeslips, by going to the past.

How to slip

In timeslips I’ve observed that the time travel itself, though tied to story in a sensible way, often occurs without too much fuss. In this case various pieces of glass, and the idea of a crack in the house, make satisfying devices. Kate Constable makes some of the slips as easy as Rowan falling asleep in her own bed and waking up in a new time, but every so often she indulges in a longer description of Rowan being seized by fatigue in the middle of the day when the “tumbleglass” snatches her out of one time and into another, and it’s an opportunity to relish her rich style.

It’s what writers do about all the other aspects of time-slipping, outside of the simple device, that can be so interesting. In Tumbleglass, an adult, Verity, not only knows about Rowan’s time travelling but also masterminds it. This might have taken from Rowan’s agency but here it’s well-balanced. Verity uses magic to ensure that whenever Rowan lands in a new time, someone from that time recognises Rowan, as if nothing odd has occurred. That particular “problem” of the time-slipping character is neatly solved. Why would a writer want to solve a potential story problem so easily? To concentrate on other, unforeseen problems. That’s where this novel takes it up a notch.

Messing with time

When Ash first goes missing from her own time, her parents are frantic, the police are called, it’s all systems go. But gradually, the other people in the house become less and less concerned about Ash’s disappearance. Soon it is only Rowan who really cares. It’s intriguing and subtle. And makes Rowan’s present time the most destabilising for her, which is clever. Kate Constable masterfully explores the effects of messing with time.

When I re-read Charlotte Sometimes by Penelope Farmer as an adult, I had to wonder how much of the identity theme I’d consciously processed at 11 and how much had just seeped in, making sense even if I couldn’t articulate it. I’ve seen Tumbleglass recommended for readers of 9+, and you’ll not hear from me that a mature and well-read 9-year-old should not read this book (nor do I think the world will come crashing down if a child in primary school reads some of the more mature phrases in this novel). But I do hope that a reviewer saying “9+” won’t stop much older readers from finding this story, because there is a richness to this book for 12 to 15 year olds, and of course for any adult time-slip fan.

There is also humour in there for the time-slip aficionado, and some excellent mum-humour through her delightful vagueness and mixed-up idioms. My favourites were “fit as a fleabag” and “wild cows couldn’t keep me away”.

For anyone who wants to write a timeslip novel, Kate Constable is an author to be studied. Here’s a final word from Kate about her work.

The time slip device can be an incredibly flexible way of telling a story and it’s one that I’m continually drawn back to. It’s a way of throwing the reader into the past, or into a slightly parallel, magical world (as in The January Stars), and it has the advantage over pure historical fiction that the ‘time slipper’ can share the viewpoint of the contemporary reader. In my first time slip book, Cicada Summer, I had fun playing with the conventions of the genre and almost turned it upside down. Tumbleglass had enough going on, with five different time periods, so I didn’t want to complicate the story any further! But I hope it might prompt readers to think about the history of their own house or neighbourhood or school and the people who lived their lives there. I do believe that the time slip story is one that will never go out of fashion — there is so much history to explore!

Here are those links to my other pieces again:

A Matter of Time written piece and podcast

Thanks for reading.