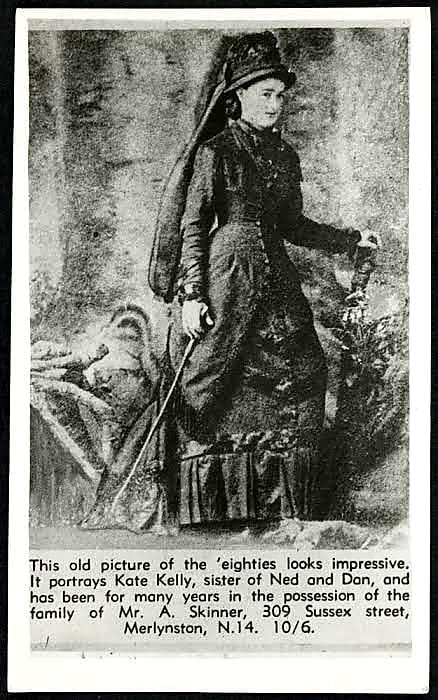

Finding Kate Kelly

Outlaw Girls is the story of a modern girl going back in time to befriend Kate Kelly, sister of Ned.

You’ve just turned fifteen. Your mother has been sent to gaol and you’re left holding a clutch of young siblings. Of your two older sisters, one died the day after she had a baby who was possibly fathered by a policeman, while another is left with two children and two unproductive plots of land after her husband is wrongly imprisoned for six years. Of your three older brothers, two are on the run with a price on their heads and the other is on his third gaol sentence.

What dreams could you allow yourself? How far might you go to protect your family?

Outlaw Girls is the story of a modern girl going back in time to befriend Kate Kelly, sister of Ned. And it’s out today.

Ned

The Ned Kelly legend is one that Australia has preserved for itself and the rest of the world to see. Born in 1854, serving long stretches in gaol as a teenager for minor crimes, such as receiving a stolen horse, an outlaw for two years and dead at twenty-five, Ned Kelly has been played on the big screen by international stars Mick Jagger (best forgotten?) and Heath Ledger (never forgotten). Ned has been held up as the almost-leader of an almost-revolution, an archetypal working-class hero. Or, he’s been vilified: Ned the cold-blooded murderer.

Ned got the Peter Carey treatment in 2000, a novel guaranteed to be massive overseas, and The True History of the Kelly Gang won The Booker, The Commonwealth, and the Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger (La Véritable Histoire du gang Kelly!). The American publisher described it as “a Great American Novel”, curiously, and called Ned “a hero of his people and a man for all nations”.

I’m not sure if Australia is done making stories about Ned – the last international movie release was as recent as 2019 – but increasingly the conversation has focussed less on Ned’s thinking and more on the people in his orbit.

Nova Weetman and I found an alternative narrative in the sisters who were left behind when Ned went on the run: Maggie, Kate and Grace Kelly all have their moment in Outlaw Girls, through Kate’s perspective.

Around publication we’re inevitably asked how we came to make Kate — middle child, superb horse rider, fifteen when Ned went on the run — the character in our second time-slip novel for older children. There’s an easy short answer: Nova suggested Kate in 2017 when we first discussed co-writing because years ago she was making a documentary about her, which remains unfinished. All I had to do was get on board.

But there’s often a longer and more complicated answer. Just for my newsletter I decided to go a bit further back . . .

Finding Australia

Spending the first thirty years of my life in England, my knowledge of Ned Kelly arrived in that nebulous way of so much childhood knowledge, right alongside Australia being known for convicts, kangaroos, much friendlier people, Edna Everidge, Michael Hutchence, and thanks to my granny’s crush on Richard Chamberlain, The Thorn Birds. In the 1980s, I’m afraid that summarises what came to mind for many British people when they thought of Australia.

When I asked my Queensland-born-and-bred partner who’d taught him about Ned Kelly – I’d assumed school or his dad – he said it was just one of those stories he’d picked up. His stock of Ned Kelly knowledge was the standard checklist: the gang, the helmet, stealing stuff, being hard to catch, and the shoot-out. Kind of a Robin Hood character, he said, and he didn’t know where he’d heard about Robin Hood either. But perhaps Ned is more like Dick Turpin, the eighteenth-century highwayman and murderer romanticised in Britain. These blokes are just part of things. Children absorb their stories from the atmosphere. My brother played Dick Turpin games with a cap gun and a broom-handle horse, a scarf tied around his face.

Aussie friends I met in London in the late 90s, when I was working in publishing, were keen to further my Australian education, inspired by the fact that I knew all the lyrics of Together Alone. Now I had an insider guide: Invasion Day, Mabo, the republic referendum, Powder Finger, The Castle, beetroot on a burger. During my first trip to Australia in 2000 I met the much friendlier people, saw the kangaroos, went to pubs and understood ‘Blow Up The Pokies’, and declared after twenty-four hours in Melbourne that I’d live there one day. Back home in London I spent my twenties watching The Secret Life of Us and failing to get off my arse to emigrate.

I was given a beautiful hardback edition of The True History of The Kelly Gang in 2001 and devoured it. There seemed to be more Australian content coming over to the UK besides Ramsey Street and Summer Bay, like Rabbit-Proof Fence, Kate Grenville, and Pinot Noir. Alone, I went to see The Whitlams in Soho after a break-up, and by then I knew who they were named after. Maybe I was the only Brit there — there were more than enough Aussies in West London alone to fill the venue. I finally emigrated to Melbourne in 2008, like I’d planned, though to be fair the universe did all the work.

In the years since, I’d seen The Kelly Gang through my children’s eyes. My youngest loved his copy of Ned Kelly and the Green Sash by Mark Greenwood, both children had trips to the State Library Victoria to see his armour, and in high school my eldest befriended one of Tim Pegler’s kids — he’s the author of the compelling YA novel Game As Ned.

But I’d still never heard of Kate Kelly.

Finding Kate

When it came to getting on board with Nova’s idea to make Kate Kelly one of our two main characters, I quickly turned into a library-dwelling Kate Kelly detective. And just as Claire Wright discovered in The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka, exploring the role of women and children during the Eureka Stockade, we found evidence of the crucial role that Ned’s sisters played during the years that the gang was in hiding.

Ned had six sisters who lived past infancy. He was closest in age to Maggie, who along with Kate, 15, and Grace, 12, were left alone at Eleven Mile Creek when The Kelly Gang was formed and were intimately involved in their brothers’ two-year fugitive life.

Ned and his brother Dan, along with their friends Joe Byrne and Steve Hart, went on the run in 1878 after they were accused of attempting to murder a police constable named Fitzpatrick. It was a crime their mother and two neighbours (including Maggie’s husband, who wasn’t even present that night) went to gaol for – matriarch Ellen Kelly was sentenced to three years with hard labour, and had to take her newborn Alice with her. The two men received six years with hard labour. Fitzpatrick barely had a scratch on him, but that whole night remains shrouded in mystery with many different, and changing, accounts.

When we looked for evidence of Ned’s sisters in Glenrowan, the small town where the gang met their dramatic end, we were excited by the slightest sign. Glenrowan is all Ned and it’s a serious tourist business. But there we were, on a scorching day, jumping for joy at an image of Kate hidden behind some sunflowers and a coffee cart, another image of Kate on the side of a pub, Kate’s Cottage which is a gift shop full of trinkets commemorating her brother, “Kate Street” running quietly off the main drag, and a simple white plate in a museum labelled “This plate belonged to Kate Kelly”.

The most compelling side to Kate’s story for me is to be found in old newspapers (thank you Trove). Kate, rather than Maggie (who was in charge of everything) was painted in the papers as a romantic figure on horseback — a pretty slip of a girl giving the police the run-around as she tore through the high country in the middle of the night. Predictably, those same papers turned on Kate after Ned was hanged – she was no longer of use to them as a mysterious figure, so where once they’d highlighted her loyalty and fearlessness, now they called her cheap and part of a disgraceful mob.

Brothers

Nova and I both grew up with brothers; we were the comparatively well-behaved siblings (though I suspect Nova had more reckless fun than I did). While we were planning Outlaw Girls we talked a lot about what it was like to worry about brothers. One of mine — the one who liked to pretend to be Dick Turpin — used to go for night-time drives down the motorway, aged 14, in my parents’ car. He’d wear one of my mum’s hats so that police would see a woman instead of a blonde teenage tearaway.

I’d never have dreamt of something like that, let alone dared to do it, for so many reasons I could have written an obnoxious essay about it while I stared at the empty driveway waiting for the car to return. It’s funny to think of him wearing my mum’s hat in the context of Peter Carey’s novel, and the subsequent movie, in which The Kelly Gang wear dresses as a disguise. Now I believe it’s more likely that the brilliant, uncatchable night riders in dresses were Kate and Maggie bringing supplies to their brothers, covering ground with a confidence the police couldn’t match.

Kate’s coming-of-age story is intimately bound to her mother’s incarceration, the burden placed on the sisters, and two years of protecting their brothers by taking them news, supplies, and even bullets. What isn’t in our novel for children is how Kate tried to shed her identity soon after Ned died, moving to a different state by herself and taking a different name. Never losing her love of horses, though sadly unable to make a career out of her excellent skills, Kate eventually married and had children. Evidently her husband was a brute. Kate lost some babies, and with her last-born probably suffered post-natal depression — she died in tragic circumstances in her thirties.

But historical fiction for children, we decided, isn’t just about the triumphant, the heroes, geniuses and royals, or working-class male heroes. In Outlaw Girls we’ve tried to tell a little of Kate’s complicated story as a young teen, and most of all to let Kate dream her own impossible things.

love thinking of you thinking of australia! australians were so scorned in my london workplace (late 90s) ‘always with the bloody backpacks’ … v. keen to read this!