Freedom, nostalgia & identity: the Penelope Farmer children's book trilogy

Notes on the Aviary Hall books

She grapples with that question we ask ourselves at puberty:

what makes me ‘me’?

“But what am I going to do with it all?” I asked my writing group as I looked over the copious notes I’d made on a children’s book trilogy most people haven’t heard of. I’d been working on them for days in preparation for a podcast about children’s classics (which I’ll link to in a later newsletter), and as usual I’d prepared enough for three podcasts, two newspaper articles and a spin-off novel.

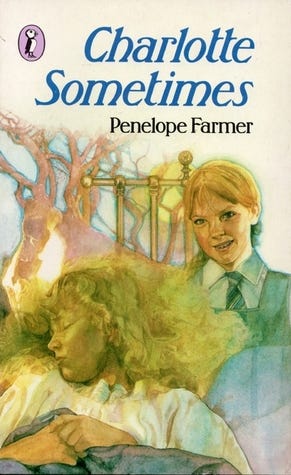

“You have the perfect outlet for it — your newsletter!” they replied. So if you want someone to blame for this obscure post, it’s them. But I hope I can make it matter to you whether or not you’ve heard of Penelope Farmer, read her children’s classic Charlotte Sometimes (1969), or the other two novels in what’s referred to as her Aviary Hall books, The Summer Birds (1962) and Emma in Winter (1966).

Penelope Farmer and The One

Born in 1939, 25 minutes after her twin, Judith, Penelope Farmer grew up in southern England, went to boarding school and read history at Oxford. She’s the author of the book I call The One, the love of my childhood, which spoke to my 11-year-old heart. That is Charlotte Sometimes, the third and final of the Aviary Hall books that Farmer wrote, though story-wise it sits between the other two.

In Charlotte Sometimes, it’s the early 1960s, and young teenager Charlotte Makepeace falls asleep on her first night of boarding school in the dorm she shares with a set of girls brand new to her, in a bed that’s somewhat different to the others in the dorm, by the window. Charlotte, a cautious, self-conscious girl, is an orphan who’s grown up with her younger sister Emma (gregarious and rebellious) in a large, dark and dusty house called Aviary Hall.

When Charlotte wakes to her first full day at boarding school, the view out the window has changed. There’s a tree that wasn’t there yesterday. More confusing is the younger girl in the bed next to hers calling her Clare. In the mirror Charlotte sees her own face but as further differences emerge she learns that she’s in the year 1918. ‘Clare’ is forty years ahead being mistaken for Charlotte, but the reader never meets her.

Over the next few weeks the girls swap every night — Clare failing Charlotte’s maths tests, Charlotte fumbling through Clare’s piano lessons. As bewildering as this is, the real trouble begins when Charlotte is in Clare’s time when she and her sister are taken in by a local family: now they are day-girls who no longer have access to the time-slip bed. Charlotte is trapped in 1918 as England copes with the final weeks of World War One.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Voracious to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.