How To Make Plot Decisions

or The Time I Killed and Did Not Kill The Dog…

Sometimes after reading a wonderful children’s book I’ll hold it quietly for a few moments, while I still belong to the story, to wonder about how an author makes so many perfect decisions. How did they get it all so right? Why does it look easy until you try it yourself? What have I still not figured out about writing for children?

Hey, Jude

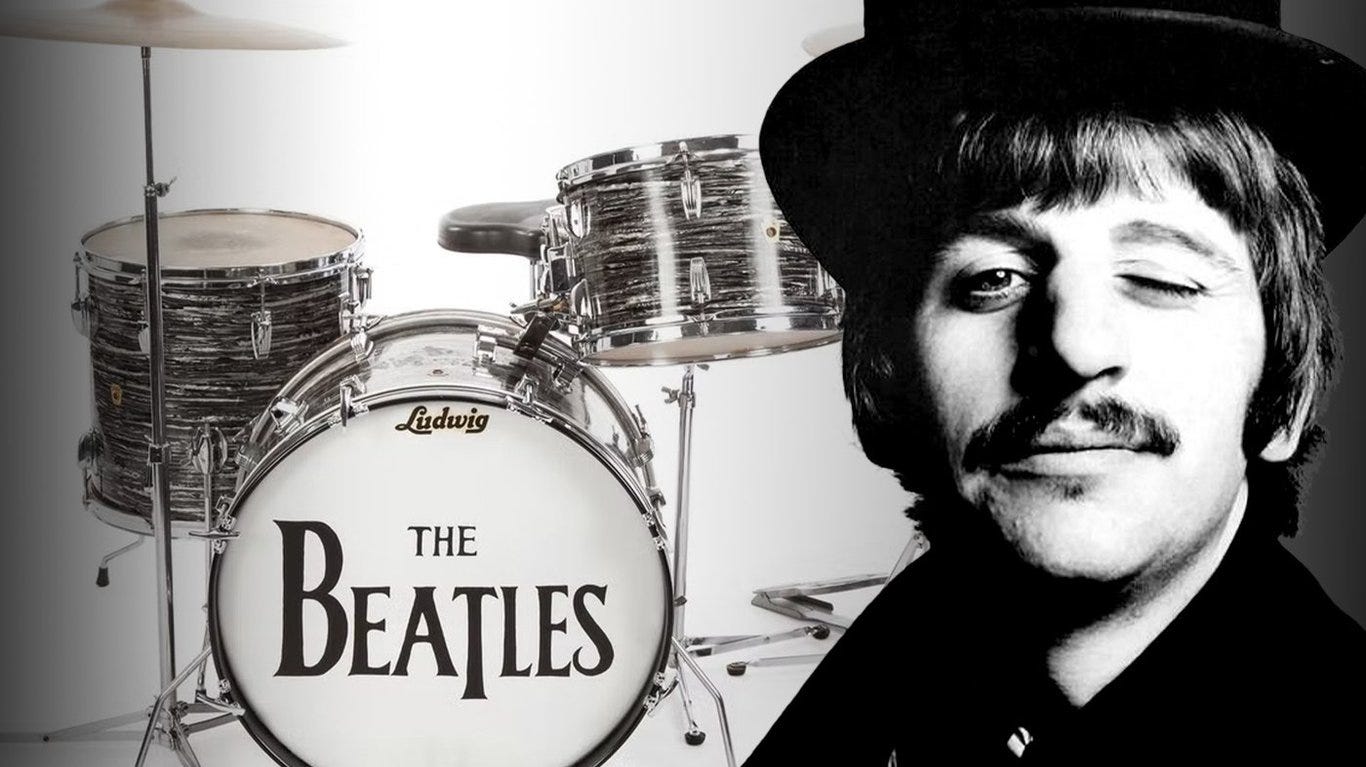

This afternoon I was distracted by an Instagram post about why the drums in ‘Hey Jude’ by The Beatles start almost a minute into the song. ‘Hey Jude’ was written in 1968 by McCartney for Julian Lennon, John’s son, around the time that John left Julian’s mother for Yoko Ono. And anytime you feel the pain, hey Jude, refrain, don't carry the world upon your shoulders. But the pause of the drums can’t claim such a poignant origin. Ringo was on a toilet break when recording began; the rest of the band hadn’t realised. He returned to the studio, picked up his sticks and joined in. It worked, so they went with that version.

Perfect plot decisions may emerge with this same sense of chance, or chaos, or they may be hard-won.

Occasionally a children’s writer — or any writer, but I’m thinking of the particular complication of making plot decisions for a young audience — will be faced with a life or death scenario: should I kill off this character or not? Because we’re writing for children we’ll ask ourselves not only is this the right decision for the story, but is it the right decision for the readership?

If we were to pay attention to all the advice about writing for kids . . .

know your audience and forget about them so you can get on with writing

never patronise your reader and also be mindful of a thousand ways you could cause them distress

tell them the truth and never be too bleak

(And somehow they pay us less even though what we do is more difficult. Alright, we can argue about that in the comments . . . )

Does The Dog Die?

I came to a point in the plot of The Goodbye Year where it had to go one way or the other for the main character’s favourite dog. Hector the Jack Russell was in trouble. The story is about a 12-year-old girl, Harper, experiencing the tumult of 2020 alongside her eccentric grandmother and five pets (three dogs and two cats). Harper had just about made it through the first year of the pandemic with Hector by her side. But I needed to resolve the storyline of another character, Will, a 14-year-old soldier-ghost who died at Gallipoli in 1915, and Hector was certainly going to be part of that resolution. The dog’s life was on the line but what was the right plot: death or rescue?

At first I was agitated by my indecision. Granted, it doesn’t take much to make me spiral in the first draft (okay, any draft). But I worried that if this decision wasn’t clear to me, perhaps that meant there was something fundamentally wrong with the entire story, all the characters, and my writing. Hmm… Naturally, I handed the problem to my writing group, also known as the two patient angels who put up with my terrible personality more than anyone else. One of them, Bronte, gave me this advice: write it both ways and then decide.

It seems obvious, doesn’t it? You can’t decide which way this should go? Write it twice! And yet it hadn’t occurred to me. I’d become snagged by the thought that if I didn’t instinctively know how the story should go, there was something wrong with me or it.

Earlier I was reading about a little-known Australian artist called George W. Bell. His paintings and philosophy of the creative life had a significant impact on his artistic friends, even if his own life’s work was relatively quiet. The Australian author Chester Eagle was one of those friends, and recalled:

“George said that if you wanted to photograph something you should walk around it, watching for the angle from which it was most clearly itself. This, if you think about it, allows for a building, an object, a person, or a scene to be itself in front of a photographer humble enough not to impose himself as well as or instead of.

This was a humility I’d always needed…”

On the occasion of deciding the dog’s fate, that is what I did: I “watched for the angle from which it was most clearly itself” by writing different versions.

Although it can frighten me to think that a story could go in so many different directions, there’s freedom in that too. To borrow a more famous line that may help when it comes to being “stuck” in your plot: “We can’t go over it, we can’t go under it, we’ve got to go through it.”

When it comes to plotting, we’ve just got to go through it. But maybe once in a while, when we’re least expecting it, we’ll be granted the magic of Ringo Starr’s ‘Hey Jude’ toilet break and the perfect creative decision will be made for us.

Love this story about Hey Jude! Plotting never gets any easier. You think it will ... but it doesn't

I have vague outlines and an order of how things happen for my current WIP but am winging it as to how I get from each point to the next.