After Jessica Miller, author of this year’s The Hotel Witch, was a guest on my podcast in August (listen here), I thought: who better to write a piece about novels with a “home away from home” setting? So grab your midnight feast and a torch and settle in.

Don’t worry, I’ll keep an eye out for Miss Hardbroom . . .

Hauntings and Hockey Sticks

So much of childhood is structured around two tensions:

the yearning for wild, rumpus-y, dangerous adventure on the one hand,

and on the other, comfort

Here is a fact about me: from the age of 12 to the age of 16, I went to an all-girls boarding school. In lots of ways, actual boarding school was far from the tuck-boxes, prefects, and lacrosse games of an Enid Blyton story. I had a modern boarding school experience — albeit modern in a way that now seems retro — replete with tamagotchis, faxed letters from family, and posters of Hanson and Leonardo diCaprio hanging in the dorm room.

But, satisfyingly enough, in other ways it really was like something out of a story. There were nuns! We played hockey! We had midnight feasts! There was an infirmary! There was an old-fashioned cage elevator! The elevator was, reportedly, haunted!

(Let me just say that while it would have thrilled me to read about a ghost haunting the halls of St Clairs, I was always petrified walking past the eerie yellow light that glowed from the elevator well if I ever had to go to the bathroom alone after lights out.)

My years of boarding school left me with a love of any dessert served tepid from a bain-marie, the ability to read a book in any amount of noise, and apparently, a compulsion to recreate boarding-school-adjacent settings in my books: The Republic of Birds features a magical boarding school, and the hotel of The Hotel Witch definitely has undertones of boarding school.

Why do we keep writing and reading these stories?

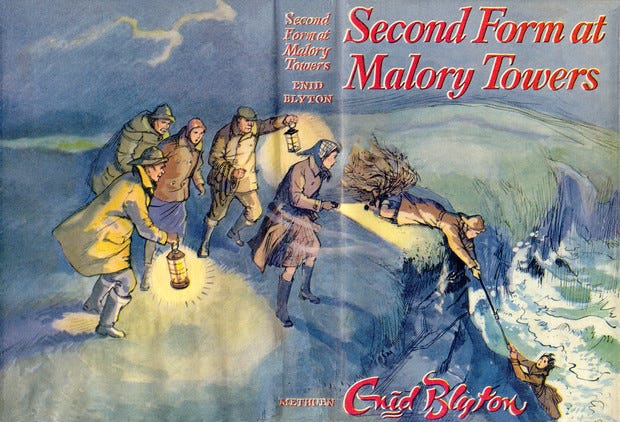

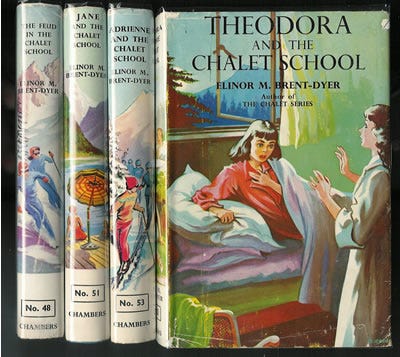

Boarding is less and less common, yet books like Enid Blyton’s Malory Towers or St Clare’s series and Elinor Brent-Dyer’s Chalet School series are considered classics. Contemporary books, like Robin Stevens Murder Most Unladylike series, have proved wildly popular over the last ten years. Boarding school stories have a weirdly enduring appeal.

Do you remember the last page of Where the Wild Things Are? (I promise this is not too much of a tangent.) Max is banished to his bedroom for behaving “like a wild thing”. After he has sailed across the sea for a year and a day and had his Wild Rumpus in the land of the wild things, Max returns to his bedroom to find his dinner waiting for him. The book’s last sentence is: “And it was still hot”. So much of children’s literature – so much of childhood – is structured around these two tensions: the yearning for wild, rumpus-y, dangerous adventure on the one hand, and on the other, comfort. Boarding school stories provide ample quantities of both.

Let there be anarchy!

Boarding school is a place where adventure is both all-but-inevitable (after all, there are no parents) but also strictly curtailed through the presence of teachers and regimented daily schedules. Even moments of real peril (remember when Mavis gets caught in a storm after she runs away to participate in the talent contest in Malory Towers?) only play out until matron notices her nightly headcount is one short. The best scenes, in my opinion, are always the prank scenes, where the balance of power tips and a hapless French teacher (always the French teacher) is deliciously outnumbered by a horde of anarchic teenage girls. If you prefer your school stories fully descended into outright chaos rather than teetering on its edge, Ronald Searle’s St Trinians cartoons or the criminally underrated movie The Hairy Bird will scratch your itch.

One of the nicest things about reading your way through archetypal boarding school stories like Malory Towers or St Clare’s or the Chalet School series is meeting the same characters over and over and finding them resolutely unchanged every time, character arcs be damned. As they progress from first form to sixth, all the girls will adhere to the label assigned to them in the first chapter of the first book – ‘sporty’ ‘swotty’ ‘bossy’ or ‘has a mysterious backstory and probably connections to the theatre or circus’. Most of these girls will be ‘real bricks’.

In every series there will also be one mean girl, who is inevitably named something droopy like ‘Millicent’ or pretentious like ‘Guinevere’. Millicent or Guinevere might be allowed to see the error of her ways in a brief scene at the end of the series, just before she gets sent to secretarial school because she has failed her final exams, but is otherwise irredeemably awful. And every book introduces a chaotic new character who shakes things up, before disappearing, never to be spoken of again – I’ve always imagined these characters must be the most fun to write. When I was writing The Hotel Witch I had great fun introducing similarly chaotic guests, though they didn’t all make the final draft.

With their unchanging casts and sealed-off settings, reading a classic boarding school story is a bit like reading a locked-room mystery, without the mystery. With Murder Most Unladylike, Robin Stevens pulls the genius move of adding a body into a boarding school story. Hazel Wong and Daisy Wells are boarders at the Deepdean School for Girls, and amateur detectives – their detective agency hasn’t had too many crimes to solve, but that changes when Hazel discovers Miss Bell, the Science Mistress, dead in the gymnasium. This book, and the ten that followed also provide a welcome update to the overwhelmingly white and straight school stories of the 1950s.

Chaos and Comfort

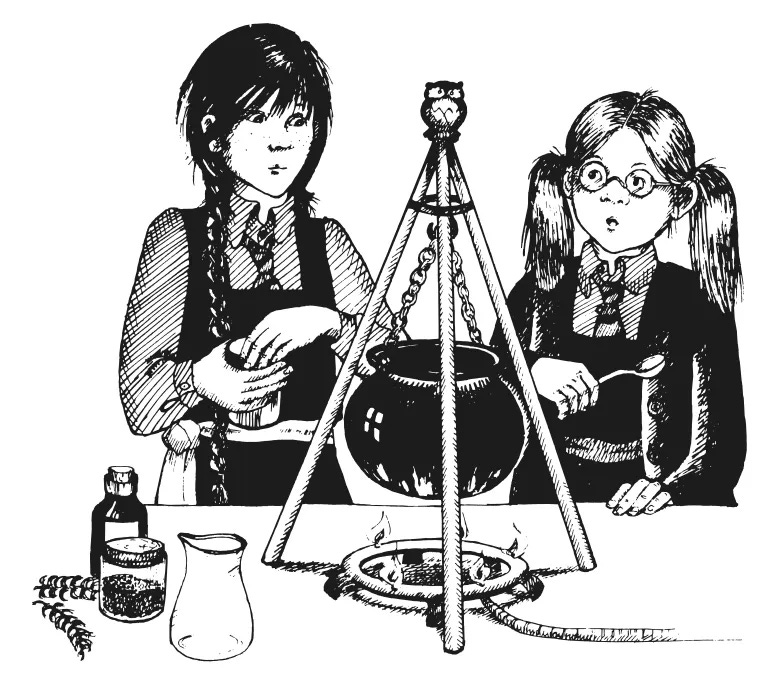

There’s a special subgenre of school story that The Hotel Witch has the most in common with – the magic boarding school. The fizz and sparkle of magic should feel all wrong set against the humdrum backdrop of lessons (okay, yes, magic lessons, but still) and communal mealtimes; instead, it's charming. I have a few theories: first of all, even though magic is inherently (I think) interesting, it’s almost always a bit boring to read about someone who is already totally competent at something: a spell gone wrong is always more fun than one that works the first time. Second, there is a beautiful parallel between the fear, wonder and transformation of mastering magic, and the fear and wonder and transformation of growing up. It’s no coincidence that so many magic school stories feature characters on the cusp of adolescence. Finally, the chaos and danger of magic is bound in a setting grounded in comfort, familiarity, and routine.

But that’s all basically beside the point. Honestly, I just love magical boarding school stories! They’re like a boarding school story but so much better. Who wouldn’t want to read about broomstick-riding lessons instead of lacrosse practice, and geomancy lessons instead of Latin study? In the past few decades, that magic boarding school (you know the one) has crowded out some other wonderful examples of the genre. So here are some of my favourites: The Worst Witch, where delightfully scatter-brained Mildred Hubble barely scrapes through her lessons; Mary Norton’s The Little Broomstick, which makes an art form of juxtaposing cosiness with menace for middle-grade readers; and Ursula leGuin’s A Wizard of Earthsea, whose School of Wizardry is solemn and serious.

YA and New Adult readers are spoiled for choice, with titles like Carry On by Rainbow Rowell, The Rest of Us Just Live Here by Patrick Ness, and Lev Grossman’s Magicians series. A boarding school story with magic elements – one that I shamefully haven’t yet read but is eloquently recommended by this very newsletter – is Penelope Farmer’s Charlotte Sometimes.

So, there it is: why I love reading boarding school stories, and perhaps an answer to the question of why, to some degree or other, I echo their structures in my own writing. The best thing about these stories is the sense that they never really finish. All the characters you’ve read about can grow up and graduate — even hapless Mildred Hubble eventually qualifies as a witch. But the corridors and dormitories of Malory Towers, Deepdean and Miss Cackle’s Academy for Witches are never, at least not to my mind, empty of students, or of stories.

JESSICA’S SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

For children and teens:

On the Jellicoe Road Melina Marchetta

Witch Week Diana Wynne Jones

Boy Roald Dahl

How to be Brave Daisy May Johnson

For adults:

Les Grandes Meaulnes Alain-Fournier

Skippy Dies Paul Murray

Frost in May Antonia White

Jane Eyre Charlotte Bronte